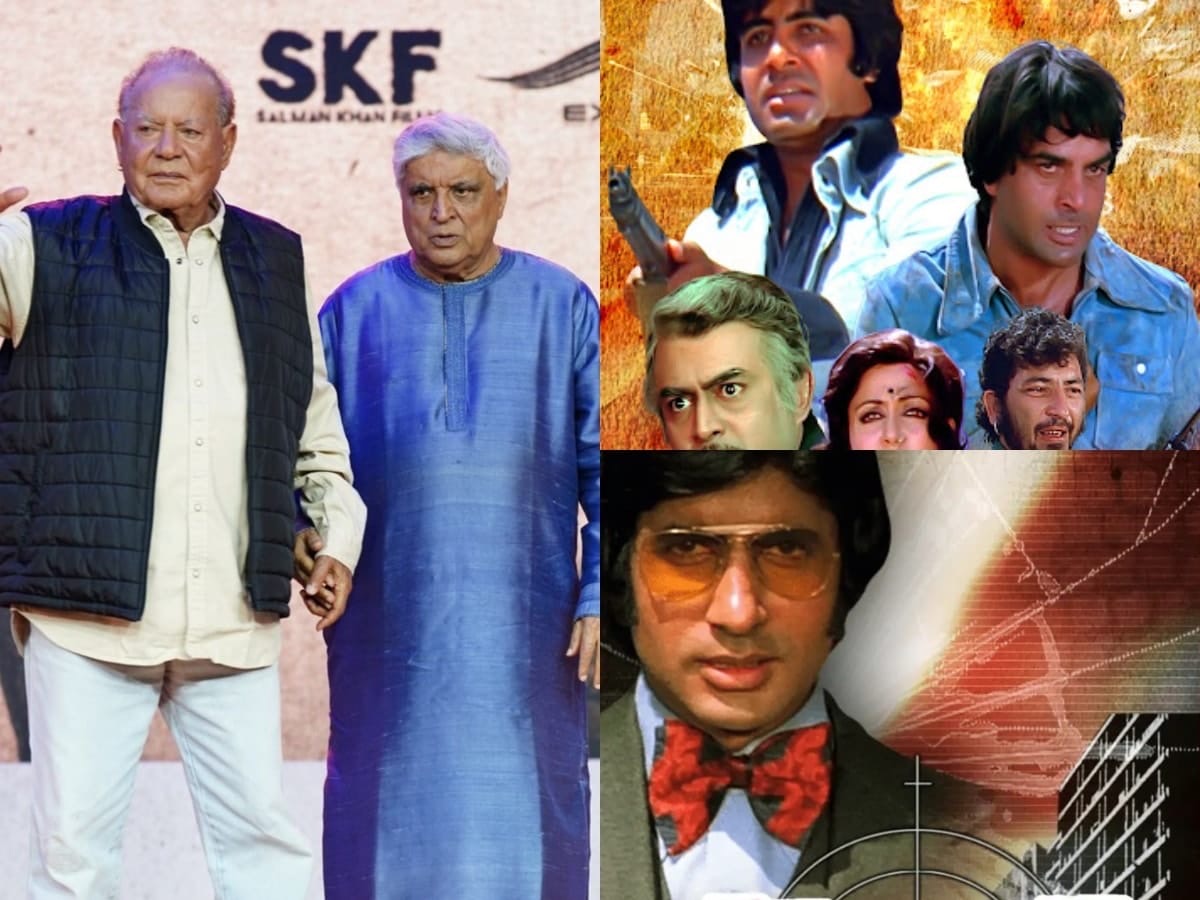

The film fraternity

let out a long breath as legendary film producer and screenwriter Salim Khan who was admitted to Mumbai’s Lilavati Hospital for a brain haemorrhage, is now stable and under observation, as per doctor’s confirmation.

At this juncture, we look back at Khan’s legendary collaboration with Javed Akhtar that delivered classics like Zanjeer Deewaar Sholay, and Don, along with several others. The two writers, who together formed the celebrated duo Salim–Javed, reshaped mainstream Hindi cinema in the 1970s and 1980s with a string of landmark films.

However, there is a particular ache reserved for partnerships that end too soon. Hindi cinema still carries it for the duo, whose split in the early 1980s and the whole country felt the cultural rupture. Long before “writer” became an industry talking point, Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar had already rewritten the grammar of the mainstream Hindi film. Their batting average was mythic. Film after film did not merely succeed; it settled into the bloodstream of popular culture.

The recent documentary Angry Young Men revisits this near-miraculous run, often through the familiar prism of the brooding, system-busting hero. But to reduce their legacy to rage alone is to miss the tonal agility that made their writing so enduring.

Even at their most combustible, Salim-Javed understood the pleasures of warmth, wit and emotional sunlight.

The list carries both the obvious entries from the Angry Young Man canon to the softer, sunnier and slyly funnier films in their filmography.

*Sholay released 1975 1975)

There is a reason Sholay feels less like a film and more like a place one has visited. Salim–Javed built its world with patience, giving every character a past, a rhythm, a line that stayed. Directed by Ramesh Sippy, the dacoit drama became an iconic tale on friendship, loss and courage, told in a language both earthy and poetic. Jai (Amitabh Bachchan) and Veeru’s (Dharmendra) silences mattered as much as their bravado, while Gabbar’s (Amjad Khan) menace came from the writing, not just the performance. The film raised the scale of popular cinema without losing its warmth. After Sholay, the idea of the Hindi film expanded. It could be epic and intimate at once.

*Zanjeer (1973)

Salim–Javed wrote Vijay as a man shaped by memory. The film stripped away the decorative excess of the period and replaced it with urgency, marking the first collaboration between the legendary writer-duo and Amitabh Bachchan, who was established as a superstar with the Prakash Mehra directorial. In the seventies, when anti-establishment sentiment was rising, Zanjeer offered a new kind of protagonist: the angry young man.

*Deewaar released in1975. The force of Deewaar comes from how intensely he understands humiliation. Vijay’s (Amitabh Bachchan) journey is not a rise to power but a response to a childhood scar that never healed. Salim Khan’s writing gave the Hindi film hero a moral fracture and allowed him to stand tall with it. The landmark confrontations amid the brothers (the other played by Shahshi Kapoor) endure because they grow from character, not design.

*Zanjeer.While the Prakash Mehra directorial Zanjeer introduced the angry young man in Amitabh Bachchan

Deewar cemented it. And Indian cinema has been rewriting that template ever since.

Don released in 1978.

*What makes Don so iconic among other things is the clarity of its writing. The double role gave the film its heart, never turning it into a gimmick. One man is feared and distant. The other is nervous, talkative and learning to survive inside a life that is not his. Salim–Javed built the tension from this contrast and kept the story moving with clean, memorable lines.

While the Chandra Barot-directorial ‘Don’

is stylish, the style heavily comes from the screenplay’s control over pace and reveal. It showed that a mainstream entertainer could be smart without losing their mass appeal.

*Trishul releasrd in 1978

turned the revenge drama into an inheritance story.

Vijay’s (Amitabh Bachchan) battle is with absence as much as with power. The writing locates the conflict in the wound carried by his mother, making ambition itself feel emotional.

Yash Chopra uses Salim-Javed’s writing as a measure of legitimacy and exclusion, where success becomes a way of rewriting a personal history and the women hold the moral centre. The film gave the mainstream narrative a new emotional architecture, where anger could coexist with longing.

Seeta Aur Geeta (1972)

Before the clenched fists and moral fury came the delicious chaos of mistaken identities. Seeta Aur Geeta remains one of Salim-Javed’s most nimble tonal high-wire acts, a film that pirouettes amid farce, melodrama and feminist wish fulfilment with remarkable ease. On paper, the premise is pure masala: separated twins, one timid and oppressed, the other a street-smart firecracker. In execution, the film becomes a sly subversion of the

good-girl/bad-girl binary that Hindi cinema had long been comfortable with. What makes the writing sparkle is its refusal to patronise either sister.

Salim-Javed lace the screenplay with situations that feel engineered for audience catharsis: the tyrannical relatives getting their comeuppance, the demure sister discovering her spine, the comic misunderstandings that spiral just enough without exhausting the viewer. Even the romance is feather-light, never allowed to swamp the central sisterhood. The jokes land clean, and beneath the laughter sits a radical idea: the woman probably doesn’t need rescuing.

Yaadon Ki Baaraat (1973)

If Hindi cinema had a family scrapbook of lost-and-found narratives, Yaadon Ki Baaraat would occupy the most dog-eared page. Yet what distinguishes Salim-Javed’s treatment is how effortlessly the film balances pulp mechanics with emotional memory. The familiar ingredients are all present: separated brothers, a traumatic childhood, destiny working overtime. But the screenplay leans into music and mood in ways that feel unusually tender for writers often associated with muscular storytelling. The title song itself becomes a narrative device, a mnemonic thread stitching the brothers back together. The writers understand something fundamental about popular cinema: sorrow must arrive in digestible portions.

The film feels like a bridge text in their career. You can sense the tightening of the revenge template they would later perfect, but here it is wrapped in melody and sentiment.

Kaala Patthar (1979)

On the surface, Kaala Patthar appears to belong squarely within the grim, coal-dusted world of the Angry Young Man era. But look closer and the film reveals a surprisingly humane core, one that prioritises collective resilience over individual swagger. Inspired by real-life mining disasters, the film gives Amitabh Bachchan one of his most internally conflicted roles. Yet Salim-Javed resist the temptation to turn the narrative into a one-man morality play. Instead, the screenplay spreads its emotional weight across an ensemble of workers, engineers and dreamers trapped beneath the earth and, metaphorically, within the system.

Shakti (1982)

A poster of ‘Shakti’Prime Video

By the time Shakti arrived, Salim-Javed were already legends, but this father-son drama revealed just how elegantly they could write emotional stalemates. The film is often remembered for its heavyweight casting, yet its real triumph lies in the moral geometry of the screenplay.

At its centre is a conflict that refuses easy resolution: duty versus affection, law versus blood. What keeps the film from tipping into operatic excess is the writers’ discipline. The confrontations are sharp but never shrill. The silences, often more telling than the dialogue, carry the ache of two men who cannot quite reach each other. Instead of engineering crowd-pleasing outbursts at every turn, they allow the tragedy to accumulate slowly. The result is a film that hurts in lasting waves.

*Mr. India (1987)

If proof were needed that Salim-Javed could do whimsy without losing narrative grip, Mr. India is the gold standard. Released after their partnership had formally ended but built on a story they had developed earlier, the film carries their unmistakable storytelling DNA.

What makes Mr. India so enduring is its tonal generosity. The screenplay moves with childlike curiosity, blending sci-fi fantasy, slapstick comedy, social commentary and emotional sincerity without ever feeling overstuffed. The invisible-man gimmick could easily have become a one-note novelty; instead, the writers ground it in the everyday struggles of an ordinary, good-hearted man. In that sense, Mr. India feels like the perfect gentle coda to a writing partnership that understood both thunder and sunlight.

News Edit KV Raman